I was already ill when, in short order, I contracted a whole host of opportunistic infections: pneumonia, esophageal candida, herpes, thrush. It was like when you see those nature films where you have a log in a forest, and you speed up the film to watch it decay. That’s what it felt like. It felt like I was drowning.

A year after my diagnosis, I was in the hospital weighing sixty-five kilos [143 pounds]. I had double pneumonia, diarrhea, and night sweats. I was told I had just a couple of months to live.

I was not long married. You talk about my life with HIV, it’s our life with HIV, my wife’s and mine together. She’s been through all the processes of dealing with me when I was really ill, and dealing with me when I was recovering, and dealing with me when I didn’t know what to do. She’s the glue that has kept me together.

I’ve had doctors say, “Well, isn’t this like diabetes?” But it isn’t. I’ve never come across a diabetic who was reluctant to tell his mother and father that he’s diabetic, who can lose a job because he’s diabetic, who doesn’t know how to tell a prospective girlfriend that he’s diabetic.

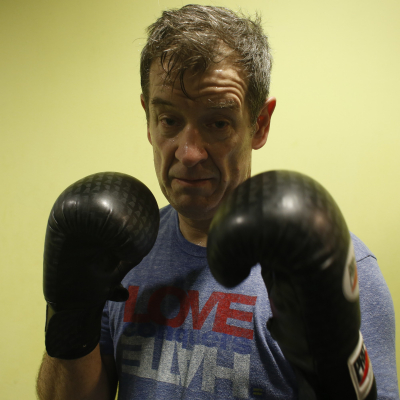

Regardless of the stigma, I have been given the gift of grace. I’m not frightened anymore.

Loads of guys got ARVs—antiretroviral treatment—and still didn’t make it. It was too late for them. It hasn’t been straightforward, coming back from the brink. The Lazarus effect is not instant. It takes time. But I want to show that, after being diagnosed with HIV, people can recover and live full, active lives.